|

Since the debate (and then the supreme court...), most of my coaching has been about the meltdown of democracy. And I am proud of the support I'm able to provide - where my coaching partners are leaving feeling empowered to take on their piece of organizing, mutual aide, community resilience, and action at the end of their sessions.

So, I want to offer this to more people. If the election has you down, I want to invite you into a special election coaching package. I am offering Defending Democracy Group Coaching weekly on Tuesday mornings at 10am Eastern from September 1 through post-election (end of November). The cost of this program is $500 total. And if you sign up in July, you can have up to 3 one-on-one coaching sessions between now and the start of the group (no additional cost). Group members can schedule additional 1:1 coaching (sliding scale $100-250/session) anytime in this time period as well, on a regular or drop in basis. First, allow me to introduce myself. I’m a fellow US American living outside the US. When my partner got offered a job in Portugal, we assessed the situation (no other jobs, gentrification pushing us out of our old city, we both already spoke Portuguese) and decided to make the move. We’re now 3 years in and building lots of community, living life well in Lisbon.

We’ve arrived at the time of year when the requests are almost daily. Friends are going to be in town, do I want to meet up? Friends of friends are coming to town and want to know what’s happening. And then the people that tell me that someone they know is moving here, and would I be willing to talk to them. This letter is to be my response to that last category, so I don’t have to repeat myself over and over again. You’re that friend of a friend. You’re tired of how things are in the US – the growing fascism and the way you and your family feel increasingly unsafe. Maybe you are queer or a “person of color” in US categories. Maybe you’re just tired of school shootings. Maybe your anxiety cannot handle it anymore. You visited Portugal (or insert other country you are considering there – I’m going to talk about Portugal, but much of this applies to most places), and you thought it was beautiful, had amazing food, and just felt so safe. You’ve researched the immigration process, and it is possible, and you want to do it. I understand. And you are a US American – which means, like me, you are a citizen of the empire. Everyone in the world learns the imperial language as Lingua Franca, and in this era, that language is our native tongue, English. By nature of your citizenship, you have access to the US economy, which means there are ways you can earn a lot of money that other people don’t have access to, and that your home currency is valuable everywhere. You hold cultural power in that our countries cultural industries are hegemonic and the whole world knows something about where you come from. The minimum wage in Portugal works different in the US. It’s a salary for full time work, includes extra months’ pay for holidays, and everyone has public health care and free childcare and paid time off for caregiving and such. But, when I have done a complicated equation, it is indeed as low as the US minimum wage, and which workers have it worse is probably the US workers, but they might have a little more cash, depending on hours worked. But, then when we look at middle class workers, in Portugal, they make more than minimum wage workers, but like twice as much, not dozens of times as much like in the US. Middle class workers do fine in Portugal’s economy, or at least they did (more on that shortly), but their wages don’t compete with the global middle class. Around now, most US American leftists bring up the brutal legacy of Portugal’s colonialism. Yes, that is true, and that wealth is embedded in some various places in Portuguese society. And, let’s be clear that there are Portuguese workers making middle class income and minimum wage, and immigrants from their former colonies and immigrants from other countries’ former colonies too. It’s complicated, for sure, but the wealth of being a former colonial power does not mean that everyone who descended from that power is wealthy, despite what our simplistic ways of thinking might tell us. So, just naming Portugal's colonial legacy does not allow you an out from the hard questions here. So, let me be clear – you will be a gentrifier here. You will look at rent and home ownership prices and be able to make it work, while Portuguese and immigrants from poor countries just can’t. Your yes pushes them out. Sure, you might have been low income in a big US city, qualifying for subsidized childcare and the like, but here your earning power puts you in the rich and you can afford things that other people can’t. You will be part of pushing out the marginalized people here – and let’s be clear those are immigrants from Cabo Verde, Brazil, Angola, Mozambique, and increasingly, Southeast Asian countries, alongside poor Portuguese people. You can indeed get around in English. You can make friends with other expats and have lovely community of similar expats – other tech workers, queer folks, Black Americans, etc. You can shop and eat out and speak English. You won’t understand the jokes about you made to your face, but I do, and people aren’t happy that you don’t speak any Portuguese. You won’t succeed at integrating, and you’ll live in a bubble. In the US, people either don’t know anyone in prison or they know a lot of people in prison because of how our race and class-based bubbles work – we don’t understand other experiences because we don’t even know they are happening. Here, you’ll be part of an elite bubble thinking things are fine when they are not. Meanwhile, everyday Portuguese voters see your presence and want an economy they can afford, and some percentage of them will then vote for a party that says “Enough!” and promises change, and happen to be far right fascists. Since I’ve been here, that party has gone from 1 seat in Parliament to 50, so I’m not joking around here. I don’t live in an expat bubble, and my relationships help me know how much of a problem expats are here We know we have economic power from my work in the US economy, despite the time zone limitations of when I can work and what I can do. We don’t know how to not be gentrifiers at all – but we work to fight gentrification. This letter is part of that fight. If you are a US American considering moving to Portugal, here’s my asks to you:

So, you’ve made it this far. It’s complicated is my answer, and I definitely think some amount of you need to just stop coming here. And there’s no right and wrong definite lines, and we must figure out how we live well in this globalized and violent world. If you are currently at risk and in danger, by all means, flee as fast as you can. But, if you aren’t in eminent danger, take a moment to really think about your impact. That doesn’t mean don’t emigrate. But I think there’s a bit more intention I’d like to see from a lot of my fellow opposition imperial citizens. May you sit in the uncomfortable questions and act with intention and care. -Claire Since the election of Trump in 2016, and even more acutely since George Floyd’s murder and the subsequent uprisings during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, organizers have faced an increasing number of polarized internal conflicts in our organizations. Maurice Mitchell described these conflicts in “Building Resilient Organizations” in 2022, identifying and analyzing many of the factors contributing to them. But even as an organizer and coach well-versed in these conflicts, I found myself surprised at how fast things escalated with a conflict of this type in my organization. As a virtual organization we didn’t have to see each other in person, and I was left wondering what might have happened if we’d been in an office. Would our communication have missed each other so much if we’d been face-to-face?

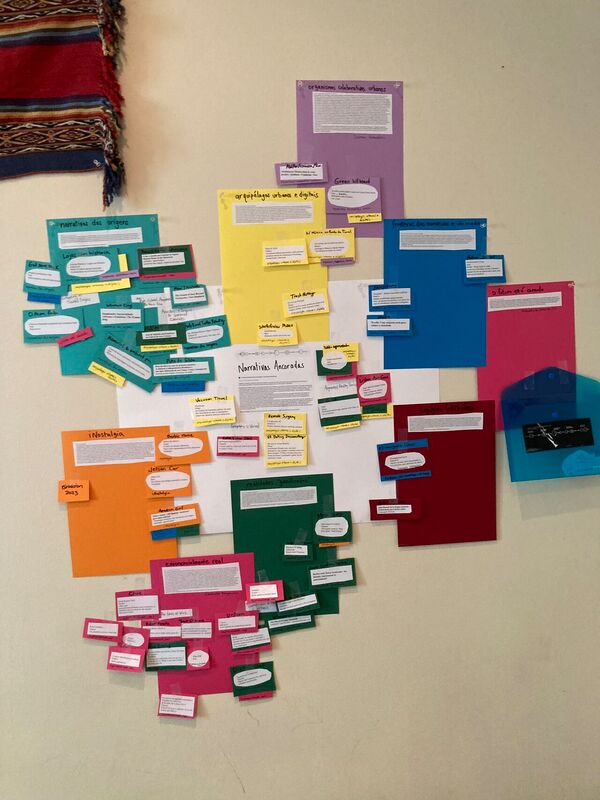

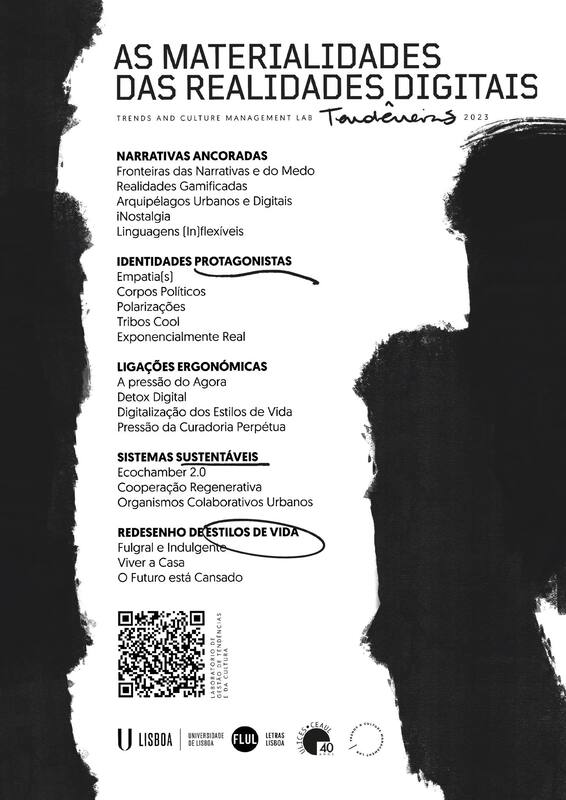

Click here to read the rest of this piece on the Forge. Going back to school wasn't something I was very sure about... but my first semester I landed in a class applying the study of cultural trends to creative projects and I immediately saw how useful it could be for community organizing. My class project work led me to a first attempt at creative campaign tactics for base building and power building. And, with my classmates, we did the research for a new trends report - a process that was an incredibly rich learning experience. The map pictured here was an early draft ... there was much color coding and I loved it! I proud to have my work featured in this report, and excited to continue my studies with my thesis project this year.

Read the whole report here: creativecultures.letras.ulisboa.pt/gtc/trends2023/

I had the pleasure of joining fellow trombonist John Covelli for this "video podcast" about trombone playing. It was a lovely conversation and I'm excited to get to share it with you.

It was not easy to get to the release of this album, and I'm proud of myself for finishing the project (finally!).

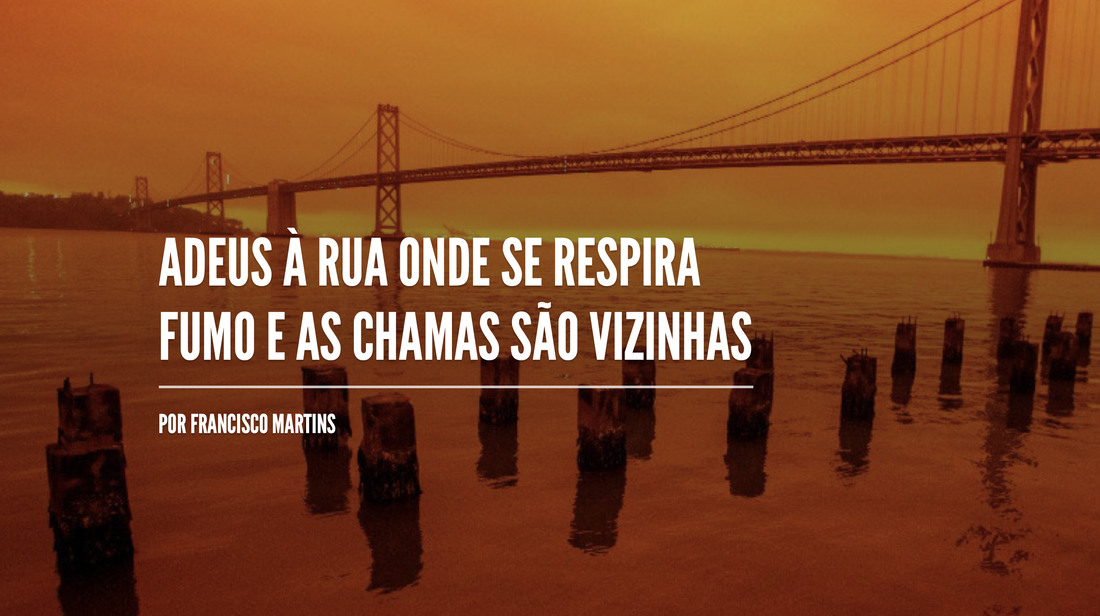

The creative aspect of improvising the music was the easy part. It was hard to get over all my internal critics about the ways I should be playing better and allow myself to be satisfied with how I was playing the week I had studio time blocked. I mixed and mastered the album myself, which while I have some sound editing chops, was a new process for me and I learned a lot. It was hard to get to text and album cover - while I had amazing photos from the original street performance project from Raquel Pimental, I needed to decide on the ones I wanted to use and design an image. I had to decide what I wanted to say. And, most of all, I had to find a way to believing that my creative voice is worth sharing - and that was by far the hardest part. I'm glad to put some art into the world. Imperfect and creative. I'm proud of this album, what's in it and behind it. Take a listen and I hope you enjoy it. Francisco Martins wrote a profile about my family's migration story and the relationship to climate change, published here for Earth Day 2022.

I'm proud to have done this interview in Portuguese and to be able to talk about important topics across languages. One of my reflections from reading this is about how by telling a story, there are stories we are choosing not to tell. There are so many other stories about climate migration that all deserve to be told this beautifully, and there are so many other parts to our story. But this story weaves a powerful narrative, part of my story, of how climate change is impacting our lives. That faint whispering that awakens us from our sleep, only to find silence:

Felt absence surrounding us again. Grief comes in waves, but the red flag has waved unceasingly for too long The crashing is loud, again and again, like curdling screams held inside us. Each of those numbers reported as deaths each day, Each of them leave someone with tears streaming down their cheeks Someone whose life feels like it is in a thick soup of cloud for the next year A whole family being knocked over by the waves, unable to swim. Dying is part of living and grief is profound. But we are in an age of such vast grief that we cannot hold it. We grieve the lives we are not living, the dreams that died. We grieve the people we have lost to death or distances. We grieve the connectedness that we no longer feel. The heart strings that weave us together are neglected, fraying. The profound beauty of grief feels blurry, and we are lost. We numb in distractions, isolated. We fall asleep, again into dreams. Instagram Live for the Sibling Transformation Project with Jeniece Stewart of Special Needs Siblings20/8/2021

I got to join Jeniece for a conversation about what we're up to at the Sibling Transformation Project and our upcoming cohort and programming. Check it out at www.siblingtransformation.org.

I don't speak French, but was interviewed by Claire Richard, to be part of a podcast in France on whiteness and anti-racist activism.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed